June 16, 2020

Poultry raisers denounced anew government claims that “deboned” meat is not “locally available” and dismissed misleading data that imports dropped in 2020 as Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) data showed it shot up 32% to 371%, including fully-finished whole chicken.

The slowdown in import arrivals claimed by the Department of Agriculture (DA) in its website statement “Drop in poultry imports bodes well for local industry” is misleading.

It was artificial as it was caused only by logistics problems due to the COVID 19 lockdown, showing a drop in imports volume from January to May.

But newly-released actual BAI data showed cumulative imports from January to May 2020 of chicken cuts skyrocketed by a whopping 140.57% to 22,941 million kilos from only 9.536 million kilos in January to May in 2019.

A perplexing data is the importation from the same period of whole chicken at 545,406 kilos, a staggering 371.43% increase from last year.

Imports of chicken leg quarters was at 43.445 million kilos for the first five months, a 45.21% increase.

Total imported chicken products ballooned to 178.334 million kilos, an increase of 50.34% from 118.616 million kilos in the same period last year.

Imports of offals grew to 1.061 million kilos or by 32.97%. Only fats and rind skin recorded decline in imports from January to May at 1.513 million kilos for fats, down by 11.68%. Rind and skin dropped by 52.19% to 398,404 million kilos.

Mechanically deboned meat (MDM) imports climbed to 108.428 million kilos, up by 45.21%.

Controversial “deboned” meat

The importation of deboned meat is a major bone of contention as UBRA said in a fresh open letter to DA Secretary William D. Dar dated June 15, 2020 that this is available locally.

Dar said earlier that DA and its attached BAI only allows importation of manufacturing inputs—mainly deboned meat– for products needed by meat processors.

But first, UBRA said in the letter that such chicken importation supposedly as “manufacturing input” has dragged down development of the poultry processing industry in the Philippines. The letter was signed by Lawyer Elias Jose Inciong, president, and Gregorio San Diego, chairman.

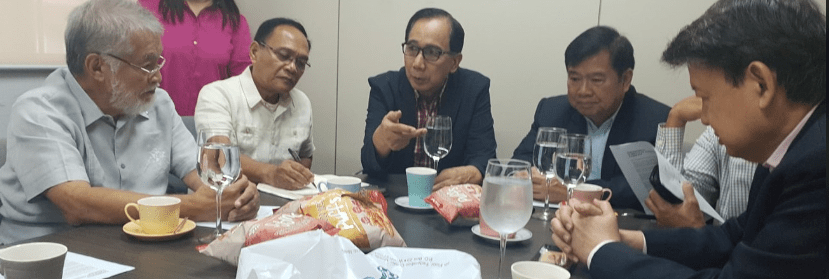

UBRA officials Gregorio San Diego, Elias Jose Inciong. Credit—DZMM, Tindig Balitaan sa Rembrandt

Already, a major company has facilities to supply part of MDM requirements with assurance of quality.

But instead of supporting MDM local production so as to develop the MDM industry and raise utilization of local chicken, DA-BAI has apparently supported imports.

“The importation agenda and mindset prevented such a development. There has been a significant increasing trend in both the total imports and the key composite items in the last five years.”

It is a blatant attempt to distort the truth that DA and BAI refuse to accept that imports have threatened the industry and jobs of local farmers and poultry raisers. That even as farmgate price of chicken collapsed to P30 per kilo during the COVID 19 lockdown.

“BAI attempts to minimize the threat of imports by saying that 70% is MDM, fats, offals, and rind/skin used by industrial processors.”

Shutdown

Worse, chicken imports in the past have already caused a shutdown of several broiler producers.

Broiler producers Purefoods, RFM-Swift, General Milling, and Robina already closed due to losses. Only San Miguel Corp. and Bounty Fresh have remained.

“Vitarich is back after suffering the ravages of importation and is now our member,” UBRA said.

“This is the reason why we cannot accept the reasoning of DA especially BAI that imports are not threat much less a cause of the sufferings of the industry. UBRA was born out of the struggle to survive such wrongheaded thinking.”

Inaction

Evidence of passive response and inaction of DA and BAI on serious concerns of poultry growers is so glaring.

In an urgent situation as the COVID 19 crisis that sent poultry farmgate price to collapse down to P30 per kilo, it took DA and BAI to respond after three weeks just to call a meeting. Its letter was on May 8; the meeting was on May 28.

UBRA denied that a “miscommunication” between UBRA and BAI happened as a video of the meeting last May 28.

“We never said that BAI gave an order to stop production. This is either a wicked spin by DA to muddle the public discourse or you were addressing other parties who have expressed their own sentiments.

UBRA stressed DA and BAI’s pronouncements clearly sent a message to poultry producers to limit production.

“We do not know how DA understands its recommendation to us that there should be “industry regulation on the level of production by each region or enterprise to prevent oversupply.”

“As chicken farmers, we understand this to mean as limiting our production to give way to imports as you feel helpless to stop it.”

Sacrificial lamb, technical smuggling

The poultry sector has been sacrificed in the country’s attempt to protect the rice sector through Quantitative Restriction or QR (restricts volume of rice imports). Tariff of MDM was offered (to WTO) to be cut to 5% for Philippines to retain the rice QR.

Unfortunately, MDM is used in misdeclaration of products.

Inciong and San Diego said Senate Committee Chairman Cynthia Villar supported UBRA’s plea for a suspension of imports upon finding out MDM is a tool in technical smuggling.

“Non-MDM items with tariffs of 40% were smuggled as were declared as MDM. The committee also found that there was no assurance that MDM was being used properly. The Food and Drug Administration said that the inclusion rate should only be 20%. The National Meat Inspection Service stated that it was alright to use 40%. The processors answered that they were using it up to 80%.”

UBRA wrote Villar a letter on May 17. The Senate office received evidence on technical smuggling from the Samahan ng Industriya ng Agrikultura .

Farmgate, retail price disconnect

It is unfortunate that both DA and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) know the disconnect between retail prices and farmgate price of products.

But they turn a blind eye in the knowledge that traders, not the farmers or consumers, enjoy the windfall profit, from low farmgate prices as these are not passed on to consumers.

“Importers are happier if wholesale and retail prices are high because they will have more margins to pocket.”

Diseases

UBRA also dismissed the position of BAI that they can only stop issuance of import permit if there are sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) questions or threat of disease from animal imports that may infect local industry.

The truth is “African Swine Fever is not a homegrown disease but an imported one. It is a major failure of BAI.”

It was even Manila Mayor Isko Moreno that led the interdiction of the entry of illegal poultry and pork products from CHIna. It was not DA-BAI despite its mandate on meat quarantine.

“These all happened because of the absence of quarantine facilities at the customs border. Stakeholders have lobbied long for its construction not BAI,” they said.

Traders’ price manipulation

Importers have gain control over prices. Because of dumping of cheap imports, local producers are compelled to reduce and stop operations.

When that happens, shortage occurs, and importers take advantage of the opportunity to raise prices.

“This is what happened in the 2003 after the Great Glut of 2002. Aside from the financial damage, imports have been the source of diseases which have decimated livelihoods in the across the countryside.”

Importers’ manipulation

The government, in its absence of devotion to local farm producers, has been made to believe by importers that they are indispensable in satisfying consumers’ demand for cheap poultry meat.

It refuses to recognize the truth that the huge volume of import is the reason why farmgate price of poultry collapsed during the COVID 19 lockdown down to P30 per kilo.

“Importers have the habit of cherry-picking high retail prices through the years to prove that they are necessary and indispensable. Look at what will happen to the consumers without us? They are blatantly silent on the very low farmgate prices which they cause that damage stakeholders throughout the value chain. From corn farmers to the wet markets.”

Passive

DA’s passive stance on protecting local farmers have relegated DA and agriculture as a less important industry in the Philippines.

“The issues we have raised are about fundamental policies and mindset. It goes beyond the poultry sector. It is probably the reason why DA is not a priority in the national budget. The absence of plans and what the Jesuits call modo de proceder, a way of proceeding, that engenders confidence in the system is the cause why we have been left behind by our peers.”

UBRA said that Philippines does not even have to resign from the World Trade Organization (WTO) to promote its local industry.

“Other countries have managed to develop under its rules. It’s just that the mindset and priorities of their agricultural authorities are not as screwed up as ours.”

“The WTO commitments have become an excuse to feign helplessness and, worse, to push for the agenda of the importers. This attitude is scandalous in its particular unfairness towards the broiler industry.”

Other agenda

These are other concerns reiterated by UBRA in its June 15 letter to DA:

- UBRA affirmed the recommendation of Senate President Pro Tempore Ralph Recto that there is a surplus in poultry.

“All of the three projections point to a surplus. If such is the case, why encourage imports? Kung 136 percent hanggang 183 percent ang chicken sufficiency forecast, bakit mag-aangkat pa?” Recto said.

UBRA said Recto’s question “crystallizes the plight of the broiler industry.”

“The pervading mindset at the DA is that it is helpless in the face of our WTO free trade commitments. It has become the perpetual excuse to do nothing and just leave farmers and producers to be slaughtered by commodities from countries with heavily subsidized agricultural systems.”

- UBRA has invoked a decision of the late Senator Edgardo Angara, when he was DA secretary in 2000-2001, to suspend poultry imports upon knowing of dumping of these products.

It was a time the poultry industry was at a “brink of collapse and had suffered enormous losses because of unfair competition from imports and smuggling.”

“This was at the height of the ideological power of free trade as embodied by the WTO. An importer took him to court but the case did not prosper. This is the reason why our members still vote for Senator Angara, the son, even though some of us are not always in agreement with him. We remember his late father.”

Yet, present DA officials ignore these issues on huge trade subsidies and support of the US and other governments to their farmers.

“Philippine agriculture has failed to flourish because the government has turned a blind eye to the subsidies and non-tariff barriers of developed countries. The United States has had several Farm Bills to support both producers and consumers. It is one of the reasons the Doha Development Round of the WTO failed.”

Trade support is “anchored on the fundamental interests of the farmers and producers.”

With full government budgetary and credit support, it has enabled “our peers in ASEAN to have successful agricultural sectors.”

“Unfortunately for the Philippine broiler industry, after Senator Angara’s very brief tenure as Secretary, the importation agenda again dominated the policy landscape.” Melody Mendoza Aguiba